(1847-present)

LITERATURE:

CARTIER – JEWELERS EXTRAORDINARY, by Hans Nadelhoffer

CARTIER 1900 – 1930, by Judy Rudoe

For many people, the name Cartier is synonymous with the finest and costliest jewelry, and evokes associations with great wealth and High Society. The house of Cartier was founded in 1847 by Louis-François Cartier (1819-1904), and was a rather modest enterprise, located at the premises of his former employer, Adolphe Picard, on Rue Montorgueil. In 1852, Louis – François set up his own shop near the Palais Royal, and later moved the shop to a larger space on Boulevard des Italiens, which was then a bustling shopping district.

At first, Cartier, like Tiffany when they first opened in New York, was mainly a retailer of jewelry and objets d’art which were supplied by a variety of manufacturers and importers. Cartier proved to be an extremely astute business man, and was soon attracting prominent clients, such as the Count of Nieuwekerke.

As Louis- François worked to establish Cartier’s reputation, he also worked to define the Cartier style. To do so, Louis-François carried pieces that combined two French traditions, bijouterie – fancy gold, enamel, and semi precious stones, and joaillerie – “high” jewelry in diamonds and precious stones).

In 1874, Louis-François’ son, Alfred (1841-1925), took over his father’s shop. The number of important clients continued to increase, and in 1899, the shop moved to the prestigious Rue de la Paix, the chic heart of high jewelry and couture in Paris. This move, combined with increasingly steadily demands from clients, both retail and to other jewelry houses, including Boucheron, Fossin, and Gueyton, prompted Cartier to expand their repertoire, and finally, to designing and manufacturing their own jewelry.

Once Cartier began to design and manufacture jewelry, the classic styles of Cartier began to emerge. Their early necklaces and bracelets were designed in the neo-Greco-Roman style, replacing the naturalistic motifs that Cartier had previously sold. Diamond solitaire earrings in silver mountings, and pearls mounted with diamonds were also signature pieces during this time. Animals and flowers became dominant motifs in pendants, and the mineral tiger’s eye was launched in Paris around 1882.

In 1898, Alfred created a partnership with his eldest son, Louis (1875-1942), who would continue to run the Paris branch of Cartier until his death.

Cartier’s designs were rapidly becoming successful and well-known throughout Europe, especially in Russsia, where their jewels were in high demand, especially by the Royal family.

In 1902, Cartier was one of the key jewelers to be called upon to design and manufacture objects for the coronation of Edward VII in London. Cartier received so many orders for the event that he decided to send his second son, Pierre (1878-1965) to London to handle the orders. Pierre’s trip to London was extremely important for Cartier, as it led to the opening of a Cartier shop in London.

The London branch of Cartier opened in 1902 and in 1906, Alfred’s youngest son, Jacques (1884-1942), became the director of the London branch. He remained there for the duration of his life.

A few years later, Cartier opened a third branch in New York City. Wealthy Americans traveling to Europe had been a large part of Cartier’s clientele from the beginning and Pierre, Alfred’s youngest son, managed this new branch.

By the time the New York branch opened, Alfred had split his company between his three sons to form three branches. While these three branches stayed within the Cartier firm, they operated independently.

At this point, Cartier had become famous for their delicate, “garland style” jewelry, which combined traditional eighteenth-century motifs of Neo-classical elements, and also motifs from ancient Greece, but in a distinctly modern and very opulent way. Cartier introduced platinum into jewelry making in Europe, although it was already in use in Russia. Platinum is light and can be thin, while maintaining its flexibility, allowing for very fine, almost invisible settings, but was challenging to work with because it could be brittle, and had a very high melting-point. The invention of the oxy-acetylene torch made it now possible to work more easily with this temperamental but invaluable metal.

Platinum was now the white metal of choice used to create the delicate styles that were newly popular. A common Cartier piece at this time would combine platinum, diamonds, and pearls worked into intricate floral designs, often with bows, flowers, diamond swags and other motifs. Sometimes, pale enamels were used, in the manner of Fabergé. They also used carved rock crystal, which added a textural contrast without adding color. Cartier made extra-ordinary chokers, sometimes using resille, a fine and flexible mesh like fabric, set with diamonds. Some of these were quite elaborate, and were worn with sautoirs or long ropes of pearls. At this time, it was not considered vulgar to show one’s wealth by wearing quite a lot of jewelry. Bracelets, long earrings, and, of course rings were worn together with several necklaces, and perhaps a diadem or tiara.

The sautoir – a long chain of diamonds or pearls suspending a jeweled element, which usually terminated in a tassel of pearls or stone beads was a new and important jewelry style that continued well into the 1920’s. The hanging ornament offered almost un-limited possibilities for exquisite designs. Tiaras were also in demand for the wealthy who regularly appeared at Royal events, and diadems, often with an Egret feather and known as Aigrettes were important hair ornaments. They became so popular that the Egret almost became extinct.

Cartier introduced another highly important design concept – they incorporated onyx into their jewelry so that it could be worn for mourning – with WW1 and the death or the King of England, there was a great demand for fashionable mourning jewelry. The black and white style proved to be so popular that it was continued as non-mourning jewelry, and became a style of its own, which continued into the 1920’s, and was used by many jewelry houses and designers for the new Art Deco look. By the 1920’s, they were already designing jewels with the panther skin motif in diamonds and onyx, a jewel that would become iconic with the fabulous Panther jewels later made famous by the Duchess of Windsor, and still in great demand today.

The discovery of Tut Ankh Amon’s tomb in 1922 created a sensation, and Cartier produced some of their most fabulous pieces in the Egyptian style, including elaborate boxes, hand-bags and clocks. Some of these pieces incorporated actual ancient Egyptian faience artifacts, such as scarabs.

Gradually, like many other jewelers, Cartier’s jewelry was influenced by India and the Far East. The “East” was a rather vague and romantic place that included China, Japan, Persia and India. Going into the 1920’s, their Art Deco jewelry reflected all of these influences, as well as the brilliant use of color introduced to Paris by the Ballets Russes. Coral, jade and lapis were combined with brilliant precious stones for brooches, bracelets, earrings, rings and compacts and minaudieres. These color combinations were new and very striking, and Cartier claimed credit for first introducing these stunning combinations of stones and colors. Hand mirrors, clocks, and table ornaments were also designed incorporating these bold colors.

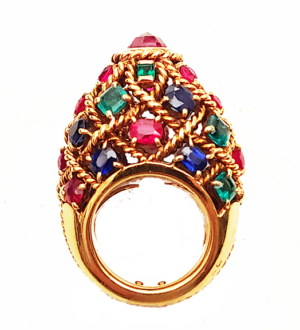

India was of primary importance. It was a source of fine colored stones, and the elaborate jewelry styles suited Cartier very well. Necklaces were bold combinations of emeralds, sapphires, and rubies – often quite large and with impressive stones, and bracelets, including the famous Tutti-Frutti, or “Fruit Salad”

were designed, using emeralds, rubies and sapphires (hence the name) set with diamonds and often accented with black enamel – stones already carved as leaves and flowers. Also from India came the Sarpeh – a jeweled ornament with a feather worn in the front of a turban. Indian royalty also became important Cartier clients.

Artier adapted the Chimera, a mythical, dragon – like beast, to create bracelets with two facing heads, often carved in coral, and embellished with onyx, emeralds, sapphires rubies and enamels. This design was emulated by other jewelers, especially by David Webb in the late 1950’s, and later with his Fantastical Jungle of animal jewelry.

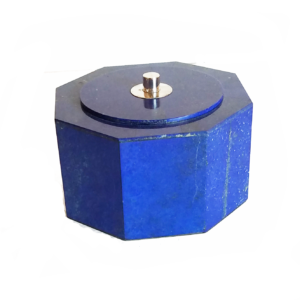

Elements from China included dragons, and scenes from Chinese life. These worked best on compacts and boxes. Sometimes old Chinese lacquer panels were used, and set into jeweled and enameled frames. Other pieces were created with inlaid materials such as ivory, mother-of pearl, coral and other colorful stones to create scenic vignettes, with elaborate mountings in the Chinese taste.

Louis Cartier was particularly entranced by Persian art. He adapted motifs from rugs and book bindings, of which he had an extensive collection, and these made for stunning inlaid boxes of all descriptions. Brooches and pendant watches were designed as fountains with birds and flowers – imagery taken from Persian gardens. Other jewelers were soon using these same motifs.

Cartier had succeeded in creating their own very distinctive style, quite different from the geometric Art Deco pieces being produced by most of the other jewelry houses. In fact, they produced little jewelry that was resolutely Art Deco.

Moving into the 1930’s, Cartier’s jewelry became somewhat less elaborate, with forms reflecting the change in jewelry styles to flatter ribbon bracelets, plaque brooches, and curves and volutes that had replaced the hard-edges geometry of much Art Deco jewelry. They incorporated more rock crystal, designing circles and rectangles of polished or frosted crystal with diamond set onyx, coral or enamel motifs on the sides, and sometimes having tassels of rock crystal, pearls and onyx. They also began using citrine and aquamarine, the newly popular stones. These were often large, calibré – cut stones that could be set flush with the setting to create a smooth, modern look, and sometimes accented with amethyst for a very original color combination.

These worked especially well for less formal jewelry, which was now almost exclusively in yellow gold, and white metal, except perhaps for evening wear, was now out of fashion. Cartier, London produced especially distinctive jewelry at this time using these stones.

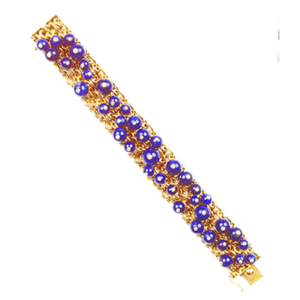

Cartier did produce some very interesting Modernist jewelry in the 1930’s – gold bracelets of complex, interlocking elements set with sapphires, flexible bracelets set with moveable lapis beads, necklaces and bracelets incorporating the “gas pipe” element of gold wound so as to produce a flexible round or flat necklace or bracelet – a technique developed by Van Cleef & Arpels, and widely adopted by just about every other jeweler. Sometimes this was set closely with round gold beads, which were on loops so as to move with the wearer. They also made pieces with gold beads having lapis or malachite “nipples”, closely set onto the gas-pipe element. These pieces were very distinctively Cartier.

The double clip was now an important jewelry accessory – the two clips could be joined to form a brooch, and these were done in curves and swirled designs, sometimes using only diamonds, but also incorporating precious stones, often calibré or cushion-cut.

Louis and Jacques Cartier both died in 1942, and Pierre to return to manage the Paris branch. Meanwhile Jacques’ son managed the London branch and Louis’ son managed the New York branch. During this time, the classic Cartier style remained true, but they became less innovative.

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor continued to be major clients, along with royalty from many other countries, especially India and the middle-east. The famous Panther jewels, designed for the Duchess of Windsor by Jeanne Toussaint, one of Cartier’s most revered designers, has become iconic; and Cartier continues to produce variations on these pieces today. They also designed tiger brooches – first made for heiress Barbara Hutton.

Their jewelry of the 1950’s while having distinctive elements of Cartier style, was more like what other jewelry houses were producing. Naturalism was now in style, and Cartier made lovely brooches with roses carved from coral or ivory, as well as beautiful jeweled flowers in diamonds and precious stones. In the 1960’s they designed a series of fabulous snake jewelry, including two very large necklaces for the actress Maria Felix. They also designed striking necklaces incorporating amethyst and turquoise, including a magnificent bib necklace for the Duchess of Windsor.

Also in the 1960’s, Cartier went back to the inspiration of jewels from India, using paisley motifs and the facing animal head bracelets, set with precious and semi-precious stones in the Indian taste. They re-visited this theme in the 1980’s. They also produced brooches of elaborate Blackamoor heads, which had been introduced by the Venetian form of Nardi. Also in the ’60’s, Cartier introduced the very popular Coffee Bean line – gold “coffee beans” were used for earrings, brooches, earrings and bracelets, with and without diamond accents.

Cartier’s jewelry, as time went by, was perhaps less innovative than in their earlier years, but always carried a certain panache that was distinctively Cartier.

Eventually, the New York and Paris branches were sold and it was not until 1979 that they reunited as Cartier Monde.

Showing all 20 results

-

$1,000,020,000.00