LITERATURE: MARCHAK, by Marguerite de Cerval, Editions du Regard.

Joseph Marchak was born in Ignatovka, a small city near Kiev, in 1854. After completing an apprenticeship at a jewelry workshop, Marchak founded his own jewelry and goldsmith workshop in Kiev in 1878.

Marchak began his business as a manufacturer, creating a gold chain as his first order. Driven by motivation and ambition, Marchak opened a second business in Moscow in 1891, and initiated interaction between the two cities. Marchak maintained control and organization over the company, and only hired people based on superior abilities. He did not depend on anyone, and oversaw all departments, which helped the company to succeed. Motivated by quality and craftsmanship, Marchak became Kiev’s most prominent jeweler in part because he paid careful attention to the details in his work.

In 1890, Marchak opened a ground floor shop so that customers could view his work in a comfortable environment. Marchak soon expanded the shop by purchasing the building next to it, opening a clock-making workshop, and also a photography workshop, so that he could take images of his work and boost sales with the production of catalogues. Lastly, he added a school where people could take engraving and design classes, or complete an apprenticeship. This program proved extremely efficient, not only providing Marchak with employees, but also benefitting women in the workforce.

Joseph began travelling to get new ideas and to find the best materials. Each time he came back, he improved his workshops and showrooms to bring them to the standards that he had seen, especially in Paris.

Marchak won many awards for his work including a medal and diploma of honor at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, a silver medal at the 1900 Paris Universal and International Exhibition, a gold medal for jewelry at the Saint Petersburg International Artistic Exhibition in 1902, and a Grand Prix at the Liege Universal and International Exhibition in 1905.

Unfortunately, the political scene began to collapse in Russia and Joseph died of illness on August 22,1918, forcing the House of Marchak to shut down.

Turmoil in Russia continued and seemed that all of Joseph Marchak’s hard work and success had been destroyed. However, in 1919, Alexander Marchak, Joseph’s youngest son, fled to Paris and opened a shop on Rue de la Paix, the fashionable heart of Paris jewelry business, and was able to revive and continue the legacy that his father had begun.

Alexander Marchak’s talent was immediately recognized and accepted, in part because of his father’s success. By 1920, Alexander became a member of the Federation for Diamond, Pearl and Precious Stone Dealers, and was one of thirty jewelers asked to display his work at the famed Art Deco Exhibition of 1925, where he won the Grand Prix.

Alexander Marchak’s work respected the original spirit of the Marchak House. Marchak’s work displayed an obvious attention to detail and craftsmanship, in addition to maintaining renewed creative thinking and originality, and an eye for modern ideas. Diversity and aesthetics trumped quantity.

The early work of Alexander is obviously influenced by the Art Deco movement in France, in addition to exotic cultures. Stylized floral motifs were often incorporated within his work. Knots, loops, or baskets often adorned engraved brooches made of precious stones. Moonstones, carved jades, and inlaid mother-of-pearl were used to incorporate Oriental motifs and designs, much as Cartier and La Cloche had done. Ribbon-rings with broad hoops and high dome-shaped mounting were created with voluminous stones and became a trademark ring that was continuously redesigned until the 1960s. Marchak’s work was dramatic without being overdone, reflecting and interpreting in an original way the taste of the period.

Marchak won the Grand Prixat the 1931 Colonial Exhibition, and enjoyed major success for his designs. When World War II broke out, however, he was forced to seek shelter in Savoy. Fortunately, he was able to keep the shop open and cared for by a trusted manager.

Once the war was over, Marchak returned as head of the shop and hired Alexander Diringer as designer, and Jacques Verger, who became head of the company in 1956. Both Diringer and Verger had studied under Pierre Sterlé. Verger was one of the most talented craftsmen in Paris, and was specially trained to make watch-cases, which is quite difficult and requires special skills. He brought these skills to the beautifully crafted jewelry that he helped to produce.

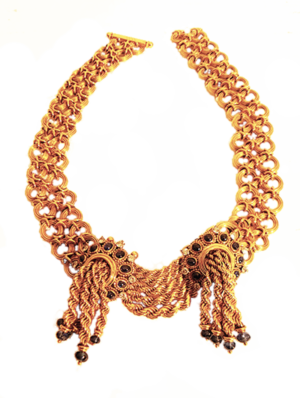

Diringer used his ingenuity and skills to create innovative designs, even though the war had caused precious materials to be scarce. New techniques including mesh weaving were invented to get around this problem, and many of the designs from this time feature smooth wires, loops, spirals, cords, or tassels which gave volume to jewelry while using as little gold as possible, and this can readily be seen in much jewelry of the later 1930’s into the “40’s.

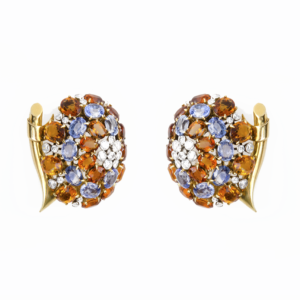

During the 1950’s, Marchak embraced the newly emerging style of themes from Nature, and animals, especially birds, floral, and vegetal motifs were mainstays of their design. Naturalistic details, also a hallmark of 1950’s, had replaced the smooth, polished stylizations of the 1930’s. Birds regained their feathers, branches were textured to look like bark, and leaves and other elements were naturalistically rendered, but Marchak also incorporated certain details that gave whimsy and movement to his designs. He used fox-tail chain as fish fins, bird feathers, stamens of flowers, and anyplace where this could add movement and dimension to the jewel. He also joined the settings of stones to be flexible, and added butterflies set en tremblant hovering above flowers. Verger favored flamboyance, which influenced the use of contrasting stones, along with the apparent disruption, dissymmetry, and slightly chaotic qualities of the pieces created during this period, but other pieces were sublimely lyrical.

French fashions became extremely popular in America during the 1950’s and 1960’s, and Verger began acquiring an American clientele, which included Jacqueline Kennedy. Verger also formed an intimate relationship with the Crown Prince of Morocco during this time, which influenced the style of Marchak with the use of Moroccan themes and materials.

In 1967, Diringer stepped down as designer, leaving Betrand Degommier as the only designer. The 1970’s designs were focused on innovative shapes utilizing stones such as lapis lazuli and citrines shaped like pyramids and octagons.

In 1988, Verger retired and sold the boutique to Daum, but the rejuvinated House of Marchak continues to exist in Paris today.

Showing all 5 results

-

$2,000,030,000.00

-

$50,000.00

-

$4,000,050,000.00