The term Art Deco was derived from L’ Expositions des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels, the famous trade fair held in Paris in 1925. It was supposed to have taken place around 1917, with the aim of reviving the waning demand for French luxury goods. World War I, of course, prevented this; and the event was finally held in 1925. Because of this delay, the style that we call Art Deco came to encompass many diverse elements, and this can make defining Art Deco jewelry confusing for many people.

One major influence was the Ballets Russes, which came to Paris in 1909, and created a sensation. The costumes were full of brilliant colors and exotic imagery. This had an immediate effect on emerging styles in fashion and, of course, the decorative arts; and provided one of the earliest and strongest influences on the style that would become known as Art Deco. There was general fascination with the “East”, which for Western minds, encompassed China, Japan, India, Persia, and, of course, Egypt, where the excavation of the Tomb of Tut-ankh-amun brought to light fabulous images that captured the world’s imagination. This created a very different style of Art Deco jewelry, which I will cover in another blog.

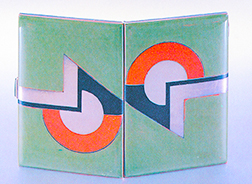

The reds and purples, greens and oranges of the exotic Ballets Russes sets and costumes, and the bold color combinations and striking designs seen in Oriental and Egyptian art were a refreshing change from the muted colors of Art Nouveau, and the unrelenting “whiteness” of Edwardian jewelry. Jewelry set with coral, amethyst, jade, turquoise, and lapis lazuli soon became associated with the new, modern style. These strongly hued stones were used to create large areas of color and texture, and could be readily carved into a variety of shapes, perfect for interpreting the infatuation with geometry that was quickly becoming a defining hallmark of Art Deco design.

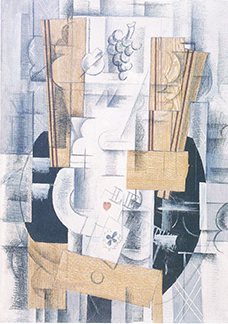

While “naturalistic” subjects, such as animals and flower-baskets could still be found, they were subjected to the rigors of geometry to make them “modern”, but often this was fairly tame, so as to appeal to clients with more traditional tastes. The greatest and most revolutionary Art Deco design, however, owed nothing to either nature or history. It drew its inspiration from Cubism. Geometric elements have certainly been present in the decorative arts and architecture of earlier and other cultures, but never in the way that we see in the early part of the 20th century.

The taste for black and white jewelry was in place well before 1925. The earlier Edwardian fashion for “white” jewelry remained a highly important presence in Art Deco jewelry style. Edwardian style (named for King Edward VII of England) became popular around 1905. Much of the jewelry in this style featured diamonds in elaborate but delicate platinum settings. The development of this style was made possible by new and practical ways of working with platinum. Platinum is brittle, and must be heated to high temperatures, but it is extremely strong. The rewards of working with platinum were settings that could be delicate almost to the point of invisibility, but strong enough to hold stones securely in their settings.

With platinum, an entire new jewelry vocabulary was possible, and every-one wanted this exciting “white” jewelry. Cartier produced jewels that made extensive use of diamonds in platinum for their Edwardian “Garland” style jewelry. By 1910, diamond and platinum jewelry was being shown with black onyx or enamel accents, and these jewels were much admired and coveted for their austere elegance. Many of these designs, such as the much-used “Greek key” motif hinted at the geometric styles to come. Jewelry set with black onyx, however, had its beginnings to serve as “mourning” jewelry. It was customary for the upper classes of “Society” to observe certain restrictions in dress and jewelry during a period of mourning. Bright color was forbidden for both dress and accessories. There were many occasions for public mourning at this time, among them, the death of King Edward Vll of England in 1910, and the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Previously, jet and black enamel had served for mourning jewelry. Now, Cartier, and other jewelry houses as well offered the fashionable woman a whole new look in mourning jewelry. Cartier expended great efforts to promote their new black and white jewelry expressly for this purpose. The terrible loss of life during WW l fueled the market for elegant mourning jewelry, and by the end of the war, the black and white look had become a jewelry style in its own right. Black and white jewelry was now fashionable for any occasion.

Jewelry set with black onyx, however, had its beginnings to serve as “mourning” jewelry. It was customary for the upper classes of “Society” to observe certain restrictions in dress and jewelry during a period of mourning. Bright color was forbidden for both dress and accessories. There were many occasions for public mourning at this time, among them, the death of King Edward Vll of England in 1910, and the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Previously, jet and black enamel had served for mourning jewelry. Now, Cartier, and other jewelry houses as well offered the fashionable woman a whole new look in mourning jewelry. Cartier expended great efforts to promote their new black and white jewelry expressly for this purpose. The terrible loss of life during WW l fueled the market for elegant mourning jewelry, and by the end of the war, the black and white look had become a jewelry style in its own right. Black and white jewelry was now fashionable for any occasion.

Long, pendant earrings in black enamel, onyx, and diamonds were the hot, new fashion accessories, as were rings with a round diamond set on an onyx plaque. Long chains, or “sautoirs” of pearls, rock crystal or diamonds and platinum supported pendants with black silk tassels. Brooches in diamonds and rock crystal were given dramatic black-enameled borders to accentuate the design. For those who could not afford the real thing, similar costume jewelry was available using silver, enamel, and “paste”, or even marcasite. Chromed or nickel-coated metal was a new and exciting development in 20th century jewelry. It was very effectively when combined with the new plastic materials, such as Bakelite and Galilite. These materials could be made to resemble semi-precious stones like lapis or coral, and especially onyx and ivory. They were perfect for the now highly fashionable black and white look. They could be readily cut or molded to any shape, and polished to a high sheen. In the hands of talented designers, these non-precious materials were used to fashion affordable jewelry of distinction that was completely modern in design and materials.

Chromed or nickel-coated metal was a new and exciting development in 20th century jewelry. It was very effectively when combined with the new plastic materials, such as Bakelite and Galilite. These materials could be made to resemble semi-precious stones like lapis or coral, and especially onyx and ivory. They were perfect for the now highly fashionable black and white look. They could be readily cut or molded to any shape, and polished to a high sheen. In the hands of talented designers, these non-precious materials were used to fashion affordable jewelry of distinction that was completely modern in design and materials.

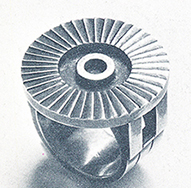

Previously, silver had been used when a white setting was desired for diamonds, but the resulting effect was heavy. White gold, a recent innovation, was also not strong enough to hold stones in delicate settings. Both silver and white gold were nonetheless very important in Art Deco jewelry because of their white, metallic sheen. They were used where the color of the metal, and it’s smooth, polished surfaces were an integral part of the design. Yellow gold was quickly going out of fashion.

This infatuation with white metals would remain a defining characteristic of Art Deco jewelry. It is rare to find Art Deco jewelry in yellow gold, although it was sometimes used as an accent, but did not come back into favor until the mid 1930’s.

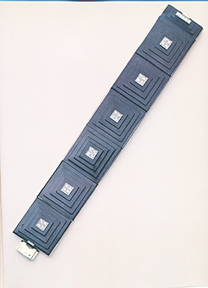

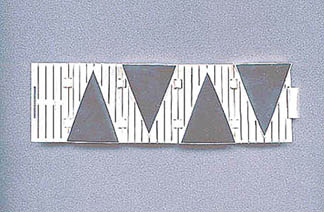

New techniques for cutting diamonds also contributed to the white look of Art Deco jewelry. Diamonds were new being cut into baguettes, squares, rectangles, triangles and half-rounds. It was possible to create a highly geometric piece of jewelry using only these stones in various geometric configurations. For the increasingly popular “black and white” look, onyx provided the perfect drama and contrast. Geometric design accents could be picked-out using finely cut baguettes and squares of onyx, set one right next to the other, in “channel” settings. Black enamel was a less costly and often more practical way of achieving the same effect, and was also used for larger surfaces, or where stones could not be used.

Black onyx does not occur naturally. Banded agate, which has black and white stripes, or chalcedony, a pale, translucent quartz, was used to make black onyx by soaking it for several months in an inky black dye created by the combination of sugar and sulfuric acid.

Long soaking was required for the dye to penetrate evenly throughout the block of quartz and turn it black. The resulting material could be carved into any shape. Round or rectangular plaques of onyx were the perfect “canvas” for Art Deco brooches, clips, pendants and bracelets, while small baguettes were perfect for accents. Black onyx was even more effective when carved into various highly three-dimensional geometric elements.

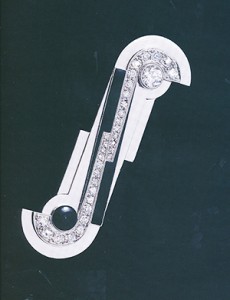

Stepped designs of concentric circles or squares provided dramatic dimension. Pyramids of onyx added a mysterious presence to a jewel.  The most rigorously geometric jewelry made use of domes, circles, baguettes, triangles, squares and other geometric shapes. These basic shapes were juxtaposed in many ways, creating strikingly powerful and original jewelry designs unlike anything previously seen. The idea of bisecting a circle and offsetting the two halves created a dynamic tension, and was very effective, as was placing a triangle or rectangle on a circle. The possibilities were endless.

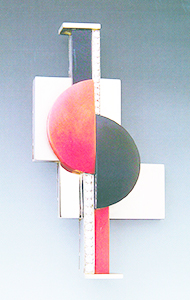

The most rigorously geometric jewelry made use of domes, circles, baguettes, triangles, squares and other geometric shapes. These basic shapes were juxtaposed in many ways, creating strikingly powerful and original jewelry designs unlike anything previously seen. The idea of bisecting a circle and offsetting the two halves created a dynamic tension, and was very effective, as was placing a triangle or rectangle on a circle. The possibilities were endless.

It is the intensity of design that gives power and emotion to these otherwise austere combinations of shapes and materials. There is a delicate balancing act between mass and movement, and the proportions have to be perfect — there are no bright colors or surface decorations to distract the eye. Since one very important aspect of Art Deco jewelry design was the lack of actual color, rock crystal became a favorite material.

This jewelry was “avant garde”, and required a client with the same artistic sensibilities. The “new woman” resembled images seen in the paintings of Fernand Legere. His women are perfectly formed, as if themselves produced by machines — their hair is milled like sheet steel into perfect waves, and they look as if they own the future. They seem to represent the aspirations of the new Machine Age generation. The Machine esthetic was, in many ways, as influential an element of Art Deco design as Cubism. WW1 had brought about many technological changes. Machines and what they could produce played a major role in the outcome of the war, and changed the way people lived, traveled, dressed and communicated.

The Italian Futurist movement was also an important source of designs. Futurist images were of things in motion – they were dynamic — hence the popularity of comets and fountains in Art Deco jewelry.

The various combinations of geometric elements provided a wealth of new and exciting possibilities for jewelry designers. Some of these designers were far bolder than others, and completely cast off the restraints of historical and natural influences. They were the “Bijoutiers-Artistes”, or Artist-jewelers, whose designs captured the essence of Cubist ideas, and translated them into something that could be worn. Raymond Templier, Jean and Georges Fouquet, Paul Brandt, Gerard Sandoz and Jean Despres are the best-known Art Deco jewelers who produced these pieces, and they are among the true pioneers of 20th century jewelry design.

The Maison Fouquet also produced jewelry that was less rigorous, and that appealed to a more conservative client who wanted to be in fashion, but not to the extreme. One of their best-known Art Deco jewelry designs was a long rope of matte-finished rock crystal beads, sometimes hanging down to the waist, with a large, glowingly translucent pendant of frosted rock crystal set with a few diamonds and, perhaps, some onyx.

During the 1930’s, the look of jewelry changed. The angular stylizations of Art Deco became chunkier and more dimensional, and the proportions of jewelry were generally heavier and more massive. White polished geometric surfaces were giving way to the sensual curves and volutes of polished yellow gold that would characterize 1930’s “Modernist” jewelry. By 1936-37, Art Deco was essentially over, and yellow gold and colored stones , especially citrine, aquamarine and amethyst were now the fashion, but the sheer drama of black and white Art Deco jewelry continues to excite collectors today with its purity of design and ageless modernity.

By Audrey Friedman, Primavera Gallery

The above blog is copyright protected, and may not be reproduced whole or in part without the permission of Audrey Friedman.